Review: Nam June Paik // Tate Liverpool/FACT // 17 December 2010 – 13 April 2011

Tate Liverpool, in partnership with FACT, is currently hosting the first retrospective exhibition of South Korean born artist Nam June Paik since his death in 2006. The exhibition is timely and stakes a claim for Paik as a visionary and pioneering artist who invented media art recognising and exploring its potential as a medium. The exhibition maps his career by showcasing ninety eclectic works that span video, performance, composing and sculpture. A purposeful chronological display, the Tate exhibition attempts to reaffirm Paik’s position within the cannon of contemporary art history. The exhibition presents Paik’s work in a chronological display that is segmented into periods of his career. The beginning of the exhibition features early works with canvas, objects and musical sheets. The exhibition illustrates the importance of Paik’s encounters with artists such as George Maciunus, Wolf Vostell and Joseph Beuys but most significantly, John Cage who had a massive impact on Paik who subsequently became a key protagonist of the Fluxus movement. The exhibition subtly hints that this is the point that Paik’s work begins to draw focus and his experimentations begin to truly push the boundaries.

Due to his relocation to New York – and with a nod in hindsight to the crowds that swamp an Apple store on the day of the release of a new gadget – Paik was able to purchase a Sony Portapak camera on its day of release and produced Button Happening (1965). The piece captures the spirit of the happenings of his previous Fluxus performance for the first time and even though the piece is ‘technically fragile’ (according to the blurb) it is vital in pinpointing Paik’s impact. A poster declaring that the advent of technology via statements carries particular resonance. An array of sculptural works featuring Eastern icons and candles being placed in situations and recorded by cameras. These voyeuristic compositions are truly prophetic about the surveillance society that engulfs us today.

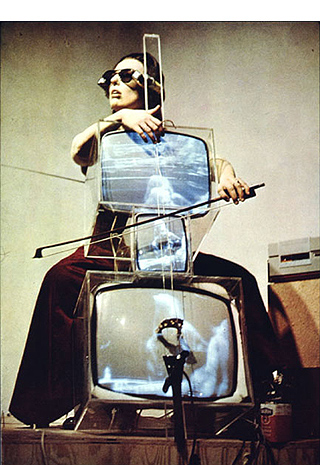

The collaboration between cellist Charlotte Moorman and Paik was a long lasting partnership that saw the two perform numerous times, often with Moorman situated playing the cello in various states of undress, the most prominent footage of her with two screens acting as a bra in TV Bra for Living Sculpture. The series of performances entitled TV Cello (1971) interestingly encapsulates the contrast between the spontaneous and performative aspects of Paik’s work and the issues that this approach raises for retrospective gallery display. The original TV Cello is displayed on the travelled wooden plinth and possesses the aesthetic fragility that a technological instrument carted around and utilised for live performances decades ago would naturally possess. The decision to pair this version with a 2003 version created by Paik is one of the exhibitions most interesting statements in terms of framing the exhibition. The replacement of 60’s screens complete with prominent cathode ray tubes with sleek black plastic coated flat screens is a nod to the possibilities of technology. One CRT remains in the new version that is covered with Perspex dubbed with paint marks. Through this action and critically a few years after a debilitating stroke, Paik acknowledges the problems of how to exhibit technology that simply isn’t built to last whilst at the same time highlighting that this situation isn’t an exclusively technological problem.

The relationship between conservation and facilitation is a necessary dialogue that quietly threads the exhibition. The use of DVD players, scart leads and amplifiers amongst the original wires is already starting to influence the display of works from the 60’s and 70’s. It is clear that as time progresses, it is going to be more and more problematic to facilitate the exhibition of these original works with modification. The question for curators of future Nam June Paik exhibitions is whether the original objects (television sets etc) are intrinsic to the nature of the work or whether or not they (or parts) can be replaced and updated? The large television work that was broken when I visited perhaps frames this question. Paik’s later works explore the relationship between nature and technology, incorporating animals and plant life. His robot series carry a universally wider appeal whilst still striking the chord of playfulness inherent in his work.

As a retrospective, the Paik show is timely and well executed. Worries that the exhibition misses important aspects of his output are levelled out by FACT’s accompanying exhibition. Laser Cone is the only work in a gallery context featured in the FACT exhibition, a work that invites the viewer to lie down and be treated to a LCD laser show. The gallery upstairs acts as an interactive library archive allowing the option to select numerous recordings either by or with Paik spanning the 70’s and 80’s. The resource is a nice touch and one can spend literally hours viewing experimental video work. Seen as a stand-alone exhibition, FACT fails to penetrate.

Accusations that the archive is inaccessible do warrant consideration but when analysed in tandem with such a clear main exhibition, the FACT archive adds worthy context to the body of work at Tate. Perhaps the ultimate complement that we could pay to the late Nam June Paik would be the ability of anyone with an Internet connection to sit at home and find his work on YouTube and view it in his or her own environment. Judging by conversations that I have had, this exhibition has been well judged in helping to give more exposure to a great artist ensuring that he is positioned accordingly.