Jack Welsh talks to Glasgow based sculptor James McLardy about his current solo exhibition White Teeth in the Planetarium at The Royal Standard, Liverpool.

Jack Welsh: What inspired the title of your exhibition at The Royal Standard?

James McLardy: The title, White Teeth at the Planetarium, comes from having read a Robert Smithson essay. In the essay, he is walking around Hayden Planetarium in New York describing the anomalies between things; a source of a fake reality and the idea of the expanded universe – but then there is a fire escape sign in the middle of the room. I was interested in this contradiction and reality. With this show, it feels like there is something alien about the work.

JW: How does the Queensway tunnel in Liverpool feature in certain works in the exhibition?

JM: When I visited Liverpool last year, I noticed the amount of 1930′s buildings in the city. Returning to Smithson, I drew on his fascination with the Art Deco period as high art as opposed to the International Style. It was a progressive period that wasn’t self-conscious of using exotic motifs in architecture. This brought me to the Queensway ventilation tower. There is a hint of the building in this work: the emerald wax I use is synonymous with what I consider to be the seedy municipality present in other central Liverpool buildings from this era. This colour provides a context without being specific, allowing visitors to make their own associations.

JW: Looking back at projects you have undertaken in other cities, you appear to engage with its architecture from your position as a visitor: do you often converse with architecture in this manner?

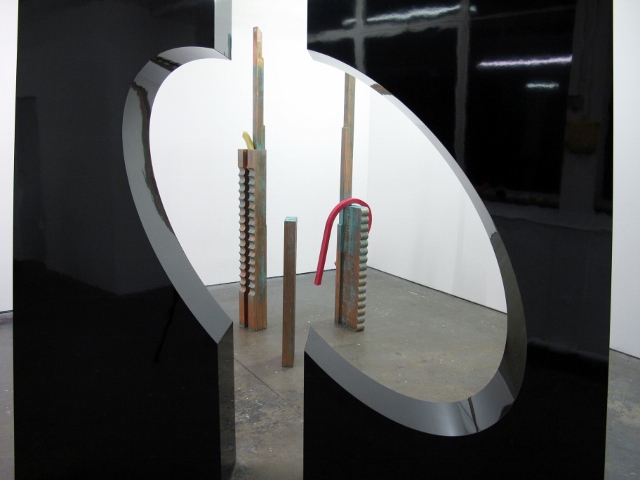

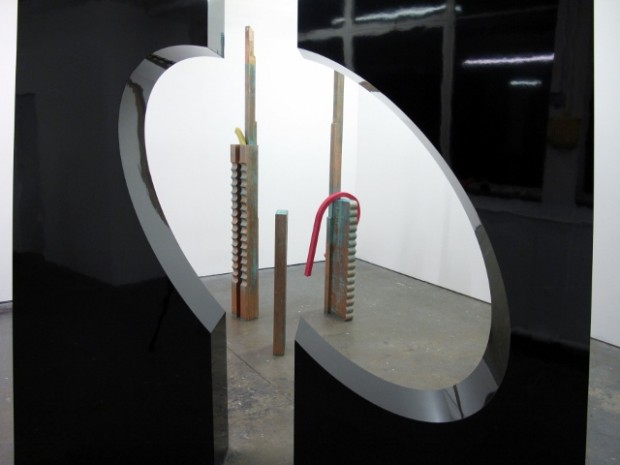

JM: I suppose it is incidental. I’m definitely interested in disturbing discipline and architecture represents a form of discipline. At the same time I strive to find a way to belittle that in architecture. In sculpture traditionally, making large works feels like a masculine ego driven activity. My work seeks to demasculate this process by attempting to pull it apart, ruin and fragment it. This has enabled me to establish an ‘other’ language, and in these works, there is an element of the dystopian.

JW: To me your sculptures are strongly idiosyncratic but they also appear to be part of a collection or installation.

JM: With this show there is an attempt to engage with a municipality. I use the language of public and classical sculpture to draw people to a collection of works that becomes an installation. However I think it is important that the room is viewed together, so yes, both.

JW: The visual contradictions of your sculpture frequently include a cerebral engagement with the plinth. How do you employ the plinth in your work?

JM: I use the traditional neoclassical plinth to subvert my installations and vice versa. A lot of artists generally engage with socialist etiquette and aesthetic but the type of work I make can’t purvey that. As I’m making the sculptures myself, I focus on using the plinth as a metaphor for what’s not there. The fragmentation in my work allows me to develop an ambiguity, such as a hint of a plinth, but it’s the space in between that is important. The lack of a plinth brings things off an imagined pedestal and allows for the subversion of hierarchy: are they plinths or are they decorative objects?

JW:Does this materialist subversion validate your engagement with modernism and other movements?

JM:When I am researching topics such as architecture, modernism or design; I’m actually just creating reference points for my work. The thing that I find it hard to explain if I am researching styles, such as Brutalism and Art Deco, is the space in between them. What is that? What does it mean? They’re the really important personal and social questions for me.

JW: Monuments are traditionally physically dominant forms that have been erected to celebrate and commemorate: they are also often representative of hierarchies of power. In what way does your work seek to engage with these associations?

JM: In a way that is where the use of facades in my work comes in. Aesthetically they are close to being an illusion or deception of these subjects. However these works aren’t just taken from real life but are rather influenced by my own thoughts or imaginings. For this exhibition, I wrote a story about two different people from two different eras on either side of modernism. One character is an actor, about 80, who was born in 1930′s and remembers the era of Lawrence of Arabia and decadent exoticism. The other is a fat balding 40-year-old motorcyclist who sits on his own at a table. You used the word idiosyncratic to describe my works earlier and I often think of my work as a combination of my own ideas with other recognisable elements.

JW: Do you consider the rich titles of your work as devices to enhance perceptions of grandeur for your objects?

JM:Definitely. With my titles, I am finding ways to make connections between the physical form and other things that I’m thinking about – or it can be another way to subvert the work. Sometimes they are just poetic, which can bring something new and hint at a wider reading of the work.

JW: Has being based at Glasgow Sculpture Studios influenced your preference of using traditional processes and materials?

JM: My work relies so much on making that if it wasn’t for the Sculpture Studios, I’d perhaps be making a different type of work, maybe with similar themes as they are an intrinsic part of my personality, but having facilities and people around has enabled this work. Without the studios it would be too expensive to make this work: but I like that contradiction. Also there is something understated about the socialist romanticism that exists in Glasgow but at the same time, there isn’t a culture of making things to a high aesthetic level in my peer group. In a way, being in Glasgow, where lots people are making different types of work, has allowed me to evolve a series of rules in my practice that has allowed me to find myself in my work.

White Teeth in the Planetarium was held at The Royal Standard, Liverpool in April 2013.