As a key crossing point on flat land near the River Mersey, Warrington’s history is built on its importance as a centre of industry. From the its origins as a market town to its role in the Industrial Revolution and beyond, Warrington’s ideal geographical location, situated between Liverpool and Manchester, has seen it prosper. Over the years, the town has displayed a canny adaptability in embracing new forms of trade and tap into technological developments in canal and rail travel. While a detailed historical summary of Warrington is beyond the scope of this text, it does set the context for the key cultural developments that eventually heralded the establishment of WCAF.

Warrington Museum & Art Gallery opened in 1848 before moving to its current site in the Cultural Quarter in 1857. Notable for its characteristic neoclassical architecture, the building is one of the oldest municipal museums in the UK. Reporting the opening of the museum, the Warrington Guardian remarked that the area ‘had one of the first buildings especially erected as a People’s Museum….let the people of Warrington feel that the Museum is theirs’ [i].

The importance of a museum and/or art gallery in educating and engendering civic pride is summarised by Weil: ‘For individuals, museums and their objects have particular meanings that are unique and allow them to experience something about themselves and their own individual identities.‘ [ii] A significant number of the 200,000 objects chronologically displayed at Warrington Museum & Art Gallery are strongly associated with the formation of the town’s identity over the centuries.

Built by merchant Joseph Parr, Parr Hall opened in 1895 as a meeting hall for the people of Warrington. In 1926, the venue acquired one of the few Cavaillé-Coll Organs allowing the venue to establish itself as a social resource akin to the Museum & Art Gallery. Over the years, the venue has hosted countless concerts from organ recitals to established orchestras. It has developed a reputation for hosting intimate gigs by heavyweight bands such as the Arctic Monkeys and, notably, the ‘second Second Coming’ of the Stone Roses in 2012.

From this historical perspective, it is evident that cultural heritage is woven into the social fabric of Warrington. The formation of the short-lived but influential Warrington Academy, an academic institution that attracted scholars from across the country, including the theologian Joseph Priestly, indicates the town’s foundation is partly built on active participation and lifelong learning. Another key cultural milestone can be traced to the 1850 Public Libraries Act, which acted as the catalyst for the development of publicly funded and freely accessible libraries. Warrington became one the first three towns in England to establish a library.[iii] While borrowers were by subscription only until 1891, the impact of such social resources cannot be understated.

Warrington expanded dramatically after its designation as part of the New Towns Act in 1968. Rapid developments in transport, including the construction of major motorways around its perimeter, saw Warrington shift towards attracting new business, retail and leisure industries at the end of the twentieth century. It was highly significant that the borough council attained the capacity to independently form policy in 1998: a move that undoubtedly led to the development of a smaller and more flexible purpose built arts centre, to complement the theatre and concert hall Parr Hall.

Securing funding from the National Lottery, Warrington Borough Council converted two disused buildings in the town centre into Pyramid: a multi-disciplinary arts centre that opened in 2002. By transforming these empty shells, problematic remnants of the town’s past, the project signalled the creation of Warrington’s Cultural Quarter; a key driver in the physical regeneration of the town centre.

In its 11 years as Warrington’s dedicated arts venue, Pyramid has been significant in shaping the cultural ethos in the town. Fusing professional performances with a healthy and eclectic participation programme, the venue has been fundamental in expanding cultural engagement in Warrington. This contribution was recognised by its nomination as a Finalist in the 2013 National Lottery Awards. Significantly, it is name of the Postlethwaite Studio, in honour of the late, great Warrington born actor Pete Postlethwaite, that provides perhaps the strongest message: talent needs to be nurtured early and given a platform to flourish.

In 2010, The Gallery At Bank Quay House, a social and commercially supported venue, opened forming a triumvirate of cultural venues dedicated to local and regional contemporary art. The gallery’s developers Python Properties were recognised for cultivating a strong relationship between arts and business by winning the national Arts & Business Corporate Social Responsibility Award in 2013. While awards aren’t the crux of cultural activities they are valuable indicators of progression; significant milestones on the journey forward.

To capitalise on this cultural momentum, WCAF was founded as a collective celebration of culture. A boost to the festival arrived in the formation of charitable cultural trust Culture Warrington in May 2012. The trust assumed management of Pyramid & Parr Hall and Warrington Museum & Art Gallery. Its ability to act autonomously outside of Local authority led to new opportunities, resulting in WCAF successfully obtaining funding from Arts Council England the first time. Strengthened by external financial support, the 2013 festival has been able – for the first time – to commission new artworks from national and international artists. The bar has been set higher.

The use of contemporary arts festivals as an instrumental cultural policy tool isn’t a new phenomenon. For centuries, arts festivals have engaged local communities and provided ‘points of meaningful connectivity and spectacle for visitors.’ [iv] From the visual arts to literature and performing arts festivals, these ephemeral and often urban-centric events promote commercial and social exchange. As the opening night of WCAF demonstrated, cultural festivals can bring out the very best in places – that inimitable buzz on the streets as hordes of people animate the public realm in search for new cultural experiences.

The proliferation of arts festivals in the UK (and beyond) since the 1980s can be attributed to what Quinn identifies as: ‘partially due to some local authorities recognizing the benefits festivals can contribute to regeneration, tourism, place image and economic development.’ [v] Quinn’s observation captures the instrumental use of culture in driving regeneration, development and ability to sell an image of a geographically defined place. This is underpinned by factors implicit in globalisation, economic production and increased ‘glocal’ competitiveness.

However it became clear over time that some festivals in the UK and Europe, due to a plethora of reasons, were guilty of lazily falling into formulaic reproduction values and – crucially – a disconnection from place. It is naive to think that applying a homogenous festival template will provide any long-term benefit after the last performance has ended and the closing exhibition has been deinstalled.

Thankfully, there is strong evidence that Warrington Contemporary Arts Festival does not fall into this trap. As noted, local engagement isn’t just one of the festival’s objectives – it underpins its entire ethos. The built environment strongly influences associations with place, yet it is the everyday nuances – the experiences that exist through human interaction – that are crucial in fostering a true sense of place. Understanding this, the festival embraces an expansive reading of culture in engaging with its locale. This is important. Understanding that wider cultural participation in Warrington isn’t purely arts orientated, but also rooted in sport and socialising, the management of WCAF rightly focuses on interacting with these value sets rather than pretending they don’t exist: a programme of elitist cultural activity simply wouldn’t work in such a civic town.

It is clear that a cultural framework on the scale of neighbours Liverpool and Manchester will never be established here. Rather than meekly allowing this fact to become a heavy millstone weighting around its metaphorical neck, Warrington has instead culturally embraced its size and independence: it is the town’s unique selling point. A focused and ambitious team of curators and arts managers has clearly played a key part in driving the recent changes forward in the wake of new administration. Yet without the trail of Warrington’s cultural history it would have been significantly harder to instigate. Memory is associated with authenticity; if culture is engrained in the genetic make-up of a town, as demonstrated earlier, then it will be in intrinsic to its future.

WCAF is the contemporary manifestation of this fact, a cornerstone of a long-term plan to nourish and develop grassroots culture in the town. The Warrington Open invites applications from artists living within thirty miles of the WA postcode. As it does in all walks of life, competitive prizes encourage local artists to raise their game while simultaneously spurring artistic activity.

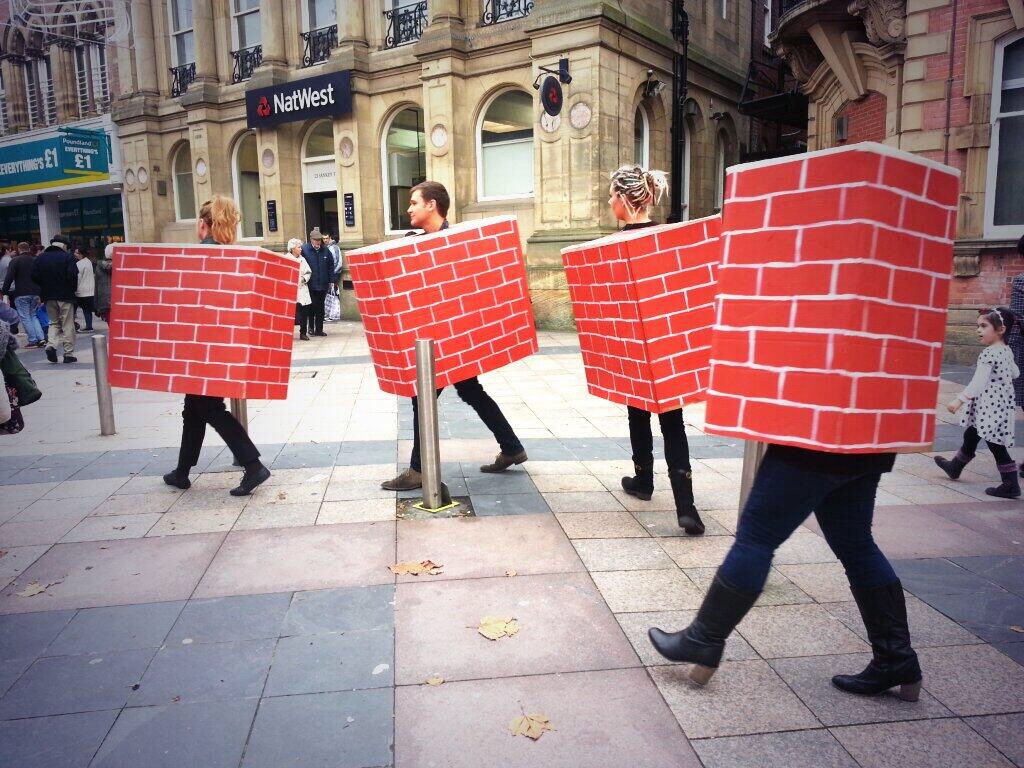

The festival applies engaged cultural production values in order to develop artworks and events that connect to local audiences, both within recognised venues and the public realm. Responding directly to the area, these commissions encourage new cultural tourism while challenging Warrington residents to reassess their own relationship to the town. Weetman’s urban drawings are inspired by local Victorian architecture and highlight urban pathways through the town. Emily Speed’s performance Brick Parade passed through the town centre on a busy Saturday afternoon. Continuing her artistic exploration of our psychological and bodily relationship to architecture, Speed’s performance took place in direct interaction with the long standing buildings in the town centre, raising questions about future regeneration plans for the town centre as well as the importance of community in civic centres.

It is possible visitors may have also encountered Jeremy Bailey’s Master/Slave Invigilator System in operation. Able to communicate with audiences through an iPad interface affixed to his ‘slave’, Bailey took residence in the town despite being physically thousands of miles away. Commissions from artists such as Speed and Bailey provide a counterpoint to the traditional sculptural monuments embedded in the town centre, providing critically engaged examples of artists dynamically intervening in the built environment.

Perhaps the most interesting dialogue of this year’s festival is the display of Polly Morgan’s taxidermy works adjacent to the paintings of Sir Luke Fildes in Warrington Museum and Art Gallery. Here cultural heritage and locality engages in dialogue with the dynamics of contemporary art. This conversation seems to reinforce the perception that for a festival to succeed – regardless of where it is held – it must forge a genuine connection with its locale but also display healthy cultural ambition.

In her opening speech of the 2013 WCAF festival, Acting Cultural Director of Culture Warrington Tina Redford indicated that the festival aimed to ‘form a creative class, not a cultural elite’ in the town.[vi] If we consider the origins of the term ‘Creative Class’, advanced by Florida, it proposes a demographic segment of knowledge workers and creative producers. Aside from cultural producers, this field encompasses workers from professional fields such as technology and education.

As Warrington adapts by seeking to attract new technological and creative industries to the area, as it did with industry many years ago, culture must be leading from the front. Recent figures released from an independent economic evaluation for the town show that tourism has increased by 13.3% – an economic success. The role of WCAF has – and will be – crucial in helping to facilitate this change long-term, by developing its programme through high quality, critical artworks and actively nourishing the development of the town’s cultural infrastructure. Naturally, this won’t happen overnight: it will take years. Yet three festivals down the line, there is healthy indication this process is on track.

Jack Welsh, November 2013